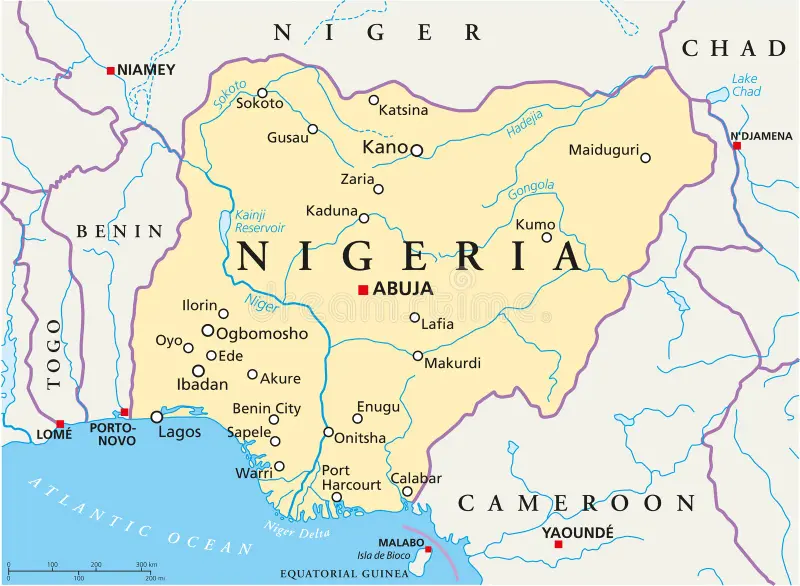

On Christmas Day, the United States carried out strikes in the Sokoto region, in northwestern Nigeria. Washington’s justifications, the lack of transparency regarding the objectives achieved, combined with the confusing statements from Nigerian authorities, have left Sahelians and observers perplexed. This lack of clarity surrounding the motivations, as well as the conduct of the operation, has given rise to multiple interpretations, thereby fueling tensions in a region already beset by numerous crises. Was this really about protecting Christians from the Islamic State, as Donald Trump declared, or should the reasons be sought elsewhere?

When Tomahawks Sow Doubt

According to the Reuters news agency, on the night of December 25 to 26, the Pentagon fired sixteen Tomahawk cruise missiles from naval platforms stationed in the Gulf of Guinea, as well as GPS-guided munitions delivered by MQ-9 Reaper drones. Still according to the agency, these strikes targeted two jihadist camps linked to the Islamic State in the Bauni forest, in Sokoto State. However, according to several Nigerian sources, villages that were hit had never reported any terrorist presence. This was notably the case in Jabo, where, according to a local lawmaker who traveled to the site, the missiles landed in an empty field about 300 meters from a local hospital, with no injuries or fatalities reported. Local representatives visited other sites and confirmed the absence of identified militants at the locations of the explosions. Lawmakers questioned the purpose of the airstrikes: “Was this an attack meant to make headlines or to send an inexplicable message?”

Similar uncertainty surrounds Lakurawa, the jihadist movement targeted by the strikes. According to James Barnett, a specialist in jihadist dynamics in the Sahel, while there are indications of links between this group and the Islamic State in the Sahel, it remains difficult to establish a direct affiliation. According to the same researcher, Lakurawa does not in fact designate a structured jihadist group; it is a generic term used locally to describe fighters from the Sahel operating in northwestern Nigeria. This label moreover covers heterogeneous realities, mixing jihadists, armed bandits, and local militias.

To this erratic military action is added diplomatic ambiguity. When Donald Trump announced the bombings on his social network on December 25, 2025, he stated that they had been carried out at Nigeria’s request. He added that the targets had been chosen to protect “primarily innocent Christians” from the Islamic State. The following day, the Nigerian government adopted a much more cautious tone, referring to intelligence cooperation and strategic coordination. Authorities were careful not to mention any explicit request or to confirm the religious dimension. Then Nigerian Foreign Minister Yusuf Maitama Tuggar stated that he had held telephone conversations with U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio just minutes before the operation, insisting that the action was not directed against any particular religion. Finally, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) modified its posts on Elon Musk’s social network: “at the request of” Nigerian authorities became “in coordination with” those same authorities. This diplomatic muddle demonstrates the embarrassment of all actors involved in a poorly planned operation. As for the Nigerian government, while it eventually endorsed the strikes, it was careful not to claim any religious character for them.

Indeed, if Donald Trump’s crusade to “save Christians” may respond to pressure from powerful American evangelical lobbies, in Nigeria it is particularly ill-timed. In Sokoto State, as in northern Nigeria as a whole, Christians are a minority, most of them living in the south of the country. They are also not specifically targeted by jihadist groups, whose violence strikes civilian populations without distinction of religion. In this respect, it is worth reading the article by researcher Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, a specialist on Nigeria, “From the United States to Nigeria, the making of a ‘genocide of Christians.’”

Therefore, if these bombings were truly intended to “save Christians,” other theaters of crisis—such as Syria, for example—would offer far more obvious justifications for American intervention. This rhetoric also contributes to creating artificial tensions between Christians and Muslims, reinforcing regional unease while fueling various theories about the real motivations behind the operation.

Hypotheses Abound

Currently, the region is experiencing a cold war–like climate between countries supported by Russia—those of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES): Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger—and Western countries. The American strikes were therefore perceived by these states as a direct threat. Niger shares a western and northwestern border with the Sokoto region, along strategic routes used by traders, criminal networks, and jihadists. Fearing they might be next in line, Nigerien authorities ordered a general mobilization as early as December 27. Often labeled paranoid, the junta in power in Niamey nonetheless has several reasons to be concerned. On the one hand, many Lakurawa militants originate from Niger. On the other, Washington strongly resented being forced to leave its major drone base in Agadez following the July 2023 coup. Finally, it was in the Nigerien capital that last October an American pilot working for an evangelical NGO was kidnapped, probably by the Islamic State in the Sahel. Nevertheless, it does not appear that AES countries were in Washington’s sights, even indirectly, especially during this period of easing tensions and negotiations over Ukraine between Russia and the United States.

A West African diplomat offers another possible explanation for the strikes. Islamic State fighters accused of killing two American soldiers in Palmyra, Syria, on December 13 are said to have managed to escape and take refuge in Nigeria. The White House would thus have carried out a retaliatory operation on Christmas Day, invoking the protection of Christians. Two birds with one stone… Except that, in general, Americans loudly claim responsibility for such actions—unless the Tomahawks missed their targets. This interpretation, however, runs into another flaw: as early as October 2025, well before the Palmyra attack, Donald Trump had already threatened Nigeria with strikes, invoking exactly the same arguments. Or was it simply a matter of reassuring the evangelical electorate on a symbolic date? At the price of Tomahawks, this would be costly communication.

Finally, it is also possible to link these Christmas bombings to the American diplomatic obsession with China. Historically considered a reliable U.S. ally in West Africa, Nigeria—the leading oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa—is asserting greater independence. Over the first seven months of 2025, its trade with China reached $15.48 billion, an increase of 34.7% compared to the same period in 2024. This spectacular rise illustrates the strengthening of economic ties between Abuja and Beijing. As a result, the Christmas bombings could resemble a warning shot aimed at this historic partner. This also recalls attacks against Venezuelan fishermen’s boats rebranded as drug traffickers by Secretary of State Marco Rubio. There are similarities between Caracas and Abuja. Both are major oil-producing countries that, for different reasons, are moving away from the dollar. In Venezuela’s case, this de-dollarization is largely imposed by U.S. sanctions, which have pushed it to rely on the yuan or parallel channels to maintain its exports. For Nigeria, it is rather a pragmatic approach. As early as 2018, Beijing and Abuja concluded a currency-swap agreement aimed at diversifying settlement currencies, reducing pressure on dollar reserves, and deepening financial cooperation with China. The agreement was renewed in December 2024. In both cases, Beijing appears as an unavoidable partner. Nigeria, Venezuela: same battles?

Whether they are a means of pressuring an ally, retaliation, or economic influence, these Christmas bombings illustrate the state of the world. A military operation terrorizing populations—one that could have major consequences in an already fragile region—is carried out in total opacity. This leaves free rein to conspiracy theories which, it must be acknowledged, are sometimes not so far removed from reality. When a single tweet is enough to trigger a tsunami and several diplomatic migraines, deciphering, analyzing, and understanding becomes a daunting challenge.

Leslie Varenne